Lessons Learned From German Football

Tonight the English football team faces Germany in Dortmund and for many fans of England, this is the most important rivalry. Although Scotland and Wales border England and could be expected to be the biggest of foes, it has always been Germany that England loves to beat. It would be refreshing to say this is simply a football rivalry, but like anything to do with England, it is a rivalry shaped by events off the pitch rather than the actions on it. In fact, it would not be difficult to argue that the English national football identity has been critically shaped by the relationship with Germany through the 20th century. Although some might point to tournaments in 1966 or 1996 or even 2010, it is of course World War II that many English football fans will reference, even when facing non-German opponents. The English brass band, to everyone's annoyance, will sporadically play the theme tune to the WWII film ‘The Great Escape' and the Dam Busters tune can sometimes be heard. When playing Germany, England fans go into WWII nostalgia overdrive, with renditions of the frankly pathetic ‘Ten German Bombers’. It was perhaps in 2010 when WWII references reached a nadir. As the German attackers battered England 4-1, the TV cameras surveyed the crowd and picked out two dejected England fans clad in RAF blue uniforms and sporting oversized fake moustaches. I would hope that as England fans we might have learned a lesson by now, but I am not overly optimistic.

What makes the continued referencing of a 72 year old war during a football game all the more embarrassing is that for Germany, England is not even the most important rival. Ask German football fans and they would more than likely point to the Netherlands as their biggest rival. Alternatively, Italy is seen by some as Germany’s bogey team, while a minority might say France. England is a rival, but not of great importance. German fans like beating England, but in the way siblings like getting one over each other. Germans like the English game, they enjoy the Premier League and older generations will mention how they always enjoyed the “kick and rush” style of physical football that England used to embody. This might be a veiled criticism of the lack of footballing technique in the English game, but it is generally accepted that English players are at their best when they are physical and fast.

On the whole, German fans wish England well, which was exemplified for me following England’s early exit from Euro 2016. If I had been in Scotland or Wales following England’s embarrassing, yet predictable defeat to Iceland, I would have taken the week off to avoid the perfectly justified crowing of rival fans. In Germany, there were wry smiles a plenty, but most people commiserated with me or stated how shocked they were at the result. Even if feigned, it was nice of them not to stand on their desks, point at me and in unison chant “Wanker, Wanker, Wanker” repeatedly until I left the room.

Footballing failure has become the pattern for England in recent years. We have gone through so many supposed “Golden Generations” and false dawns that enthusiasm is surely now at an all time low. It is always at these low points that fans, pundits, players and managers will look to Germany and their resurgence since Euro 2000 and ponder what England can learn from Die Mannschaft. The current England managerial incumbent, Gareth Southgate, has continued this Teutonic musing saying England must “get off the Island” and learn from countries like Germany in order to fulfil their potential. I would think that most football fans would agree, but they would also note the up hill struggle that England faces. As Southgate commented "We've probably got some work to do”.

The work in question starts at the top. At the end of last year, three former Chairmen of the FA and two former executives wrote to the Culture, Media & Sport select committee to complain that the FA itself was "unfit for purpose", with grey haired old men, vested interests and the power of the Premier League preventing fundamental changes from occurring in the national game. This is in stark contrast to the Deutsche Fußball-Bund (DFB), who have reorganised their youth systems and structures, while retaining the support of the Bundesliga. The call for change in the English game is almost an annual event and yet it has still not managed to understand what Germany has proved possible, namely that national footballing success comes from everyone pulling in the right direction and investing in youth players and coaching.

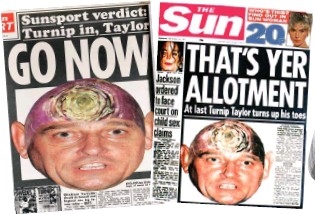

Although changes need to be made at the top, there are also fundamental changes needed in the mentality of the English media. Watching England lose to Iceland, it was clear from the reactions and body language of the players that they were terrified to make any kind of mistake. The fear of errors, I would argue, stems from the continued reaction of the English tabloid media. If England win, they are the champions in waiting, footballing giants. Should they lose however, the media will hang them out to dry, call them turnips and watch in delight as their effigies are burnt around the country. The English tabloids seem to revel in the failures of the English team, perhaps angry football fans buy more papers. Although the German media is tough on their national team, they do not intentionally will them to lose. They certainly would not publish the tactics of the team before a crucial game, as tabloids did before England faced Russia last year.

Changes in organisation or in the media mentality will have an impact, but it in the end, it is the players who must be able to perform. England are capable of producing talented footballers, but it is perhaps more than talent that footballers need to succeed. In Germany, there is a focus on creating the right mentality in young players. Freiburg are an excellent example of how to shape young players. Although they know their youth teams need a will to win, they also know that winning is not always the most important. Freiburg demand young players train hard, but that they also learn hard. Pressure is not placed on children to perform at the highest level, first and foremost they should enjoy playing football. Only when children qualify for the under-12 level, do things get a little tougher. Even though the training becomes more professional, the focus is still towards personal development. Academic ability is given equal time to be developed, something that the English game forgets. The experience of Freiburg youth coach Christian Streich is one example of the major differences in youth development:

“When I went to Aston Villa eight years ago I told them our players, under-17, 18 and 19, go to school for 34 hours a week," he says. "They said: 'No, you're a liar, it's not possible, our players go for nine hours.' I said: 'No, I'm not lying.' They said: 'It's not possible, you can't train and do 34 hours of education.' I said: 'Sure. And what do you do with the players who have for three years, from the age of 16 to 19, only had nine hours a week of school?

"They said: 'They have to try to be a professional or not. They have to decide.' I said: 'No, we can't do that in Freiburg. It's wrong. Most players in our academy can't be professionals, they will have to look for a job. The school is the most important thing, then comes football.' We give players the best chance to be a footballer but we give them two educations here. If 80% can't go on to play in the professional team, we have to look out for them. The players that play here, the majority of them go on to higher education. And we need intelligent players on the pitch anyway.”

There are many comparisons to be made between English and German football and certainly much to be learned from the way Germany organises, supports and produces football players. However, it must be remembered that there are some things that cannot be changed. The German language might be the final reason that Germany has seen such footballing success, especially in penalty shoot-outs. When English football fans talk about penalties at any level, there is a certain ache and certainly a sense of foreboding. It is safe to say the English don't like the word penalty, which hints at punishment and retribution. However, in Germany penalty is translated as Elfmeter or 11 meters, the distance from spot to goal. There is no emotive element in consideration. When it comes down to it what are you more scared of? Penalties or eleven meters. Perhaps then, Germany’s great success is a secret of language.