Germany and Static Trends

Many years ago, 1998 to be exact, I took part in an exchange program that brought me to Germany for the first time. Frankly, I was shocked. Throughout my German lessons at school, my fellow pupils and I had been exposed to numerous images of Germany via our textbooks. These pictures showed children that looked very similar to ourselves, except they all appeared to be living in the 1980s. Big hair, shoulder pads and acid washed jeans appeared to still be in fashion. We would make fun of Germany for being so out dated, so behind the times, in Britain we were modern, in Germany they were living in the past. Imagine, then, our surprise once we arrived in Germany to find that it actually looked very similar to where we had just left. No perms or jehri curls on display and definitely no shell suits.

Our German hosts were equally at a loss, they had expected us to look like we were walking off the set of an episode of ‘Saved by the Bell’. When I asked my exchange partner why he thought this, he opened his school bag, produced his English textbook and showed me a series of pictures that seemed to prove that Britain was perpetually stuck in the eighties. It was in that moment that I realised both mine and my German exchange partners schools were in dire need of more modern learning materials.

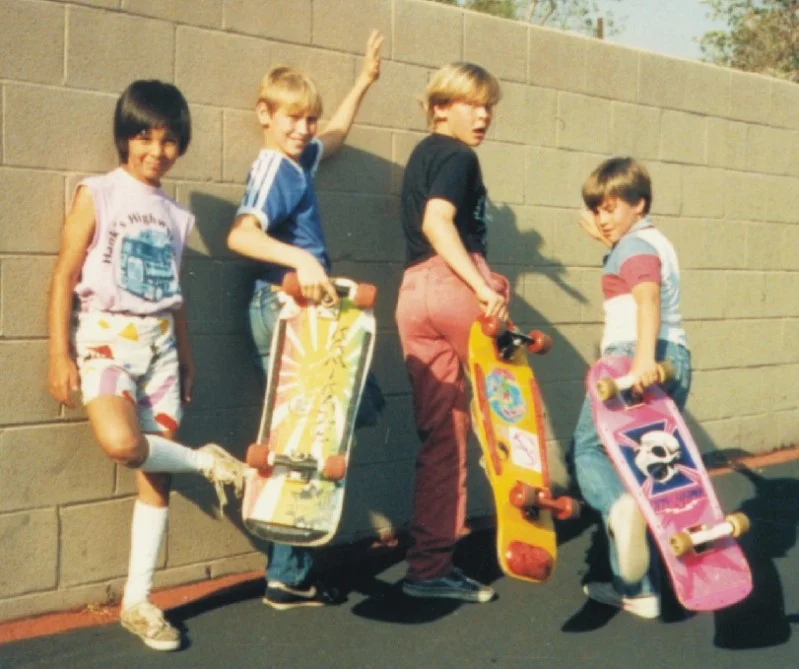

The idea that Germany is somehow stuck in the past is a common misconception, especially among the British. People are always curious about the popularity of David Hasselhoff and are slightly dismayed to discover that the American crooner is no longer a household name. People outside Germany still see the Federal Republic through the lens of outdated school books, a version of Germany that is still wearing leg warmers unironically and men wear oversized suits with the sleeves rolled up.

Yet, there is a particular cultural nuance that allows Germany to retain past trends and enjoy them as much in 2017 as they were enjoyed in the 80s, 90s and 2000s. Take as an example, the humble roller blade. The era of roller-blades has passed for most people in the UK, save for some small hold outs and extreme sports aficionados. Yet, as the weather in Germany improves, out come scores of roller blading fans, some doing it as an exercise regime and others as an effective means of transport. At some point, Germans decided that roller-blades or inline skates were fine, they did what they needed to do and they were fun, why bow to the tectonic plates of fashion trends? If you like them, you like them and that is all that needs to be said.

This German cultural version of “it ain’t broke, so why fix it?” extends to many areas of culture. Turn on a radio in Germany and you are just as likely to hear Justin Bieber as you are to hear Pink Floyd. While researching this article, I looked up the current playlist on the nationally popular Antenna radio station. Harry Styles and Calvin Harris where sandwiched between 90s alt-rockers the New Radicals and Katrina and the Waves. It is not the case that Antenna does not have the money to update it’s playlist, but rather that these songs are still enjoyed by younger, as well as older, listeners.

Turn off the radio and switch on the TV and you will find the same phenomena. One of the most popular shows in Germany is Tatort, essentially a crime procedural drama that has a revolving cast of characters and which focuses on different regional police forces each week. Tatort has run continually since it was first aired in 1970, an incredible feat for any television show. In the UK we have long running soap operas or shows such as Doctor Who, but these shows are continually revamped, recast and modernised in the hopes of increasing viewing figures. Watch Tatort today and it is essentially the same show as it was 47 years ago, even down to the main titles. Sure it has embraced modern technology both in production and within the stories themselves, but there is a continuity, especially among the cast. Contrast that with Doctor Who, the long running sci-fi epic, which is practically unrecognisable from earlier iterations that were more famous for wobbly sets and rubber alien masks than for cutting edge special effects.

Germany is comfortable retaining what the British might perceive to be unfashionable trends. When I was recently in the UK, I was killing time wandering around the numerous vintage shops in Newcastle, andI came across a studded leather jacket, complete with arm tassels. “How eighties is that?” I overheard someone say, “No way would anyone pay to wear that!”. I silently laughed to myself, remembering how only a week before in Germany I had seen a lady, wearing almost exactly the same jacket finished off with a Bonnie Tyler haircut, quietly waiting for a bus. Germany has no problem with fashion stasis.

The UK, at least in my experience, has a totally different perspective on trends. Often the British are drawn to the modern, the most fashionable or the most up-to-date. Whether that is bushy beards, veganism or artisan bread, Britain embraces the new at the expense of the old, until they decide that the old is now fashionable and the new is passe. There are always fashion re-duxes, but often with allowances for the modern. Vintage is popular now, but can we guarantee it will be the same in one, three or five years time?

In fairness there will always be people in the UK and Germany that will seek out the new and the current, while others are left behind, but in Germany the new and the modern are best exemplified by cities such as Berlin, Hamburg or Munich. These cities are the entry points for the newest trends, but Germany is not a land of cities in the way the UK is. Germany currently finds 75% of the population in cities, whereas the UK sees 85% of the population living in urban areas. This suggests that trends have an easier chance to spread in the UK, whereas Germany has areas that either miss or simply ignore the popular cultures of the city. Yet the trends that spread to Germany are not so easily disposed of, static trends, like Bonnie Tyler hair, are here to stay.